There was nothing subtle about the messages conveyed on more than 200,000 posters produced by the U.S. government during the Second World War. As an example:

“I GAVE A MAN! Will you give at least 10% of your pay in War Bonds?”

Americans responded overwhelmingly. Of the nearly $300 billion that the war cost the U.S., about $200 billion was raised through bonds.

During World War II, propaganda, through the efforts of the Office of War Information (OWI), rallied Americans not only to buy war bonds, but to save such materials as metal and rubber, to produce their own food (“grow your own, can your own”) to work with the Red Cross Nursing Service, and, especially, to keep quiet. The slogan on one poster, “We Caught Hell!—someone must have talked,” encompasses much of OWI’s efforts at that time—to prevent careless leaking of information to spies.

The OWI, set up by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in June 1942, focused on controlling the message of the war. Government posters effectively delivered on that mission. Once produced, they were displayed and distributed across the country, in post offices, railroad stations, restaurants, retail stores, and schools.

David Orzeck, MD, was a patriot and a practicing doctor in Brooklyn. During World War II he got an assignment from the Office of Indian Affairs to go to the Makah Indian reservation in Washington state to address that community’s medical needs. “The country meant a lot to him, I could see how these posters appealed to him,” says Orzeck’s daughter Lida. Her father was a collector by nature, she recalls, and of the items he was drawn to, government war posters were near or at the top of the list; he amassed a collection of about 800 WWI- and WWII-era works. And he meticulously maintained the items as they had been distributed, Orzeck says, carefully storing them in brown paper, tying them in twine, and arranging them in batches.

And so they remained for decades. Orzeck, a busy entrepreneur who is the co-founder and CEO of lingerie and sleepware company Hanky Panky, was unaware of the precise nature of the collection until the early ’90s. Though she acquired the posters in the early ’70s when her parents moved from Brooklyn to North Miami Beach, the bundles remained unopened. “I have some of my dad’s collecting genes,” she says. “As I moved from apartment to apartment, they came with me. In 1985, I moved to a sizeable house in White Plains; there they went into a storage closet.”

In 1991, Orzeck decided to examine the packages she had given little thought to. She soon became determined to research and learn about the works, assess their value, archive and store many of the posters properly, and understand more about her father’s interest in them. But since David Orzeck had passed away in 1983, questions about why and how he came to collect them would go unanswered. “I don’t know how he had pieces from World War I,” says Orzeck. “He was a teenager then. This wasn’t a kid who was interested in art, I’m sure of it. That’s the question I’m so sorry I didn’t get an answer to.”

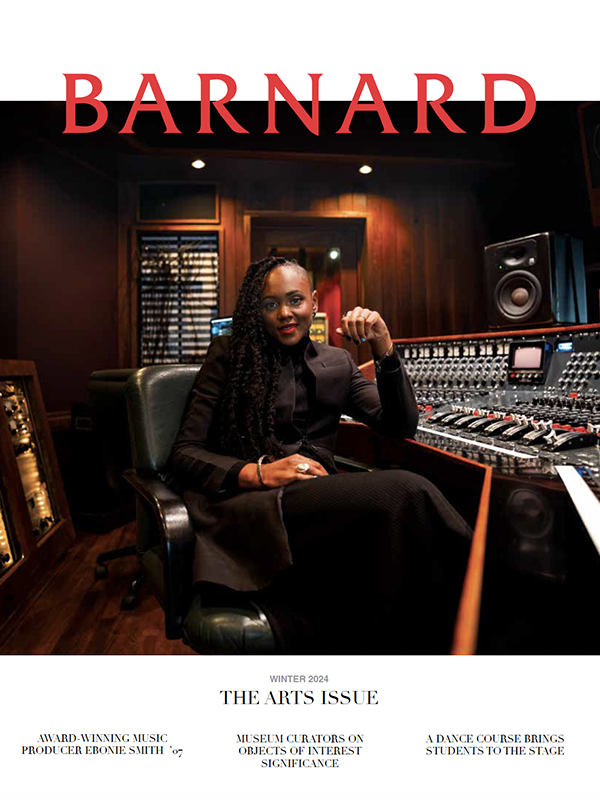

That year, 1991, was the starting point of a process that led, most recently, to her decision to donate 52 works from the collection to Barnard College Archives and Special Collections. In 2012, Orzeck, working closely with curator Steven Berger, decided to disseminate them, selling some, donating others, identifying a philanthropy to benefit from the sales proceeds, and more. There was no question about a gift to Barnard. Her alma mater is “one of her greatest loves,” says Berger, who is also a close family friend.

Orzeck and Berger made sure to donate works that would resonate at the College. With men off fighting the war, women were largely on their own on the home front, so the messages were aimed predominantly at female audiences, notes Lisa Norberg, dean of the Barnard Library and Academic Information Services. As Berger notes, while it wasn’t exactly a time of full parity for women and men, the propaganda in the posters displays messages of equality—not just gender equality but racial, too.

Much of that equality stemmed from the job opportunities created during World War II. The war created a chance for women to go to work—especially at industrial jobs—and the war posters drove women into America’s factories. (Think Rosie the Riveter.) The messages were effective. The number of working women increased from 14,600,000 in 1941 to 19,370,000 in 1944, according to Allan M. Winkler, a distinguished professor of history at Miami University in Ohio, in his 2007 essay, “The World War II Home Front.”

That is one aspect of women’s and American history now available for Barnard students, faculty, and others to explore through the new poster collection. “We hope to broaden the definition of the archives in the life of the College,” Norberg says. “We’ve expanded that to include more special collections, and we’re seen increasingly as a repository of more primary sources for use in class.”

Norberg expects the Orzeck gift will likely be used in a range of classes, from art and art history—established artists, from Norman Rockwell to Allen Saalburg created the works—to women’s studies and American history. And, as part of a larger body of research complementing other existing collections and the archive’s offerings, the posters will contribute to making Barnard more of a research destination for visiting students and scholars. That’s a main goal for the archives going forward, explains archivist Shannon O’Neill. “I see our growing expansion of what we collect as something really exciting.”

Seven World War II posters given to the College in memory of Dr. David Orzeck by his daughter are on exhibit in Milbank Hall outside the president’s office.