To honor Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, in this special edition of "Break This Down," Professor of History Dorothy Ko and Visiting Professor of Professional Practice Meg McLagan, who teaches English and film studies, offer a peek into ancient and modern-day Eastern culture and politics.

According to the Library of Congress, Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month takes place in May for two reasons: May 7, 1843, marked the immigration of the first Japanese citizen to the U.S.; and on May 10, 1869, the transcontinental railroad was completed, mostly by Chinese immigrant workers.

Dorothy Ko, Professor of History

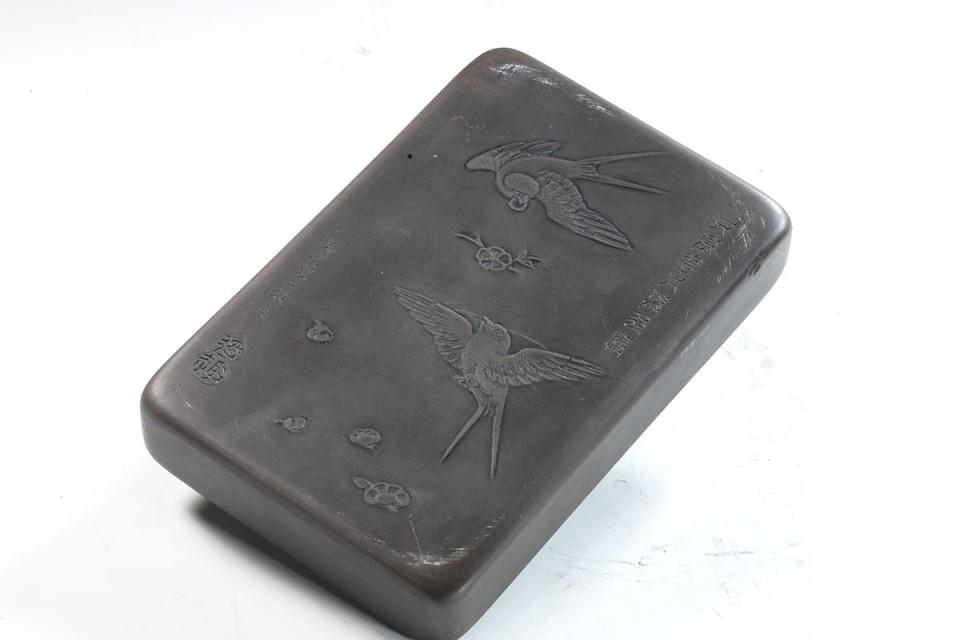

Professor Dorothy Ko explores the subjects of gender and body in early modern China. In her books, Ko unravels the complex worlds of Chinese footbinding (Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding), fashion (Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet), and feminism (Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China). Her latest, The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China, introduces the West to the world of ancient Asian stones and includes close to 100 images (see slideshow below). Ko explains the significance of this highly specialized art form.

What exactly is an inkstone and what is its significance in East Asian culture?

What exactly is an inkstone and what is its significance in East Asian culture?

An inkstone is a piece of polished stone about the size of an outstretched palm. Before the invention of fountain pens, let alone laptops and iPads, every student, writer, or painter in East Asia had to grind a fresh supply of ink at the desk by dipping an ink-stick in water and rubbing it on the surface of the stone. This process was as instinctive to them as recharging our iPhones is to us. Day in and day out, the writers and painters developed deep attachments to their implements. More than an instrument for writing, the inkstone was a collectible object of art, a father’s gift to his school-bound son, a token of friendship, and even a diplomatic gift between states.

Why is this tool so unfamiliar to Western civilizations when it has represented so much for the East for more than a millennium?

Europeans drew ink from an inkpot so they had no use for an ink-grinding stone. Nor did the early European collectors appreciate its subtle beauty as the Chinese connoisseurs did. The color of the inkstone tended to be deep purple or black; it is small and does not display well in a stately home or fancy apartment. So it is no wonder that there is no notable collection of inkstones in Europe or America.

Your book shines a light on craftswoman Gu Erniang who became famous for her inkstone-making skills, which were refined between the 1680s and 1730s. What made her such a standout?

Her extraordinary skills. Gu Erniang was a remarkable woman who thrived in a field dominated by men; she became more famous than her male colleagues. Her name was associated with technical and artistic innovations as well as refined taste. It is also interesting to mention that she enjoyed more gender freedom than her genteel sisters in that she could receive male patrons in her studio to discuss commissioned projects face-to-face.

How has the significance of inkstone artisans changed over time?

Gu Erniang was one of the first inkstone makers in China to attach her signature mark on her work, suggesting a heightened respect that exceptional artisans like her enjoyed. Today, because the inkstone is no longer a functional object, all inkstone artisans have to present themselves as creative artists.

What interests you most in this topic area and what are some of the biggest "ah ha!" moments you had conducting research for the book?

I love all the modern conveniences we enjoy but increasingly feel the need to look back and reassess the heavy price we pay for such “industrial development” or “progress.” I became interested in the craftsmen because theirs was a sustainable livelihood that was environmentally responsible. Through their eyes, I arrive at tentative answers to my big question at the moment: What makes work meaningful? The craftsman’s answer: Making one-of-a-kind objects with attention and skill in a collaborative environment. Craft makes us more human by inspiring us to strive for perfection.

How does the research conducted for this book connect to research from your previous publications on footbinding and Chinese feminism?

As a historian of gender, I’m sensitive to power inequalities and trained to analyze the operations of power. In the same way that I had retrieved women in Chinese history in my earlier books, I set out to retrieve the artisans from erasure in the hands of male scholars. Little did I know that the latter turned out to be a far more difficult project.

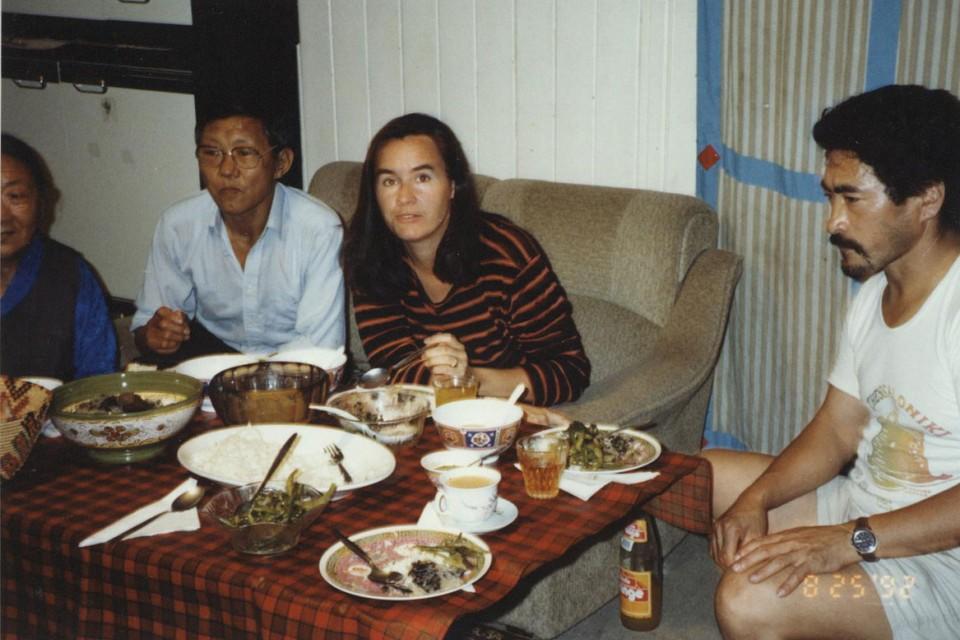

Meg McLagan, Visiting Professor of Professional Practice

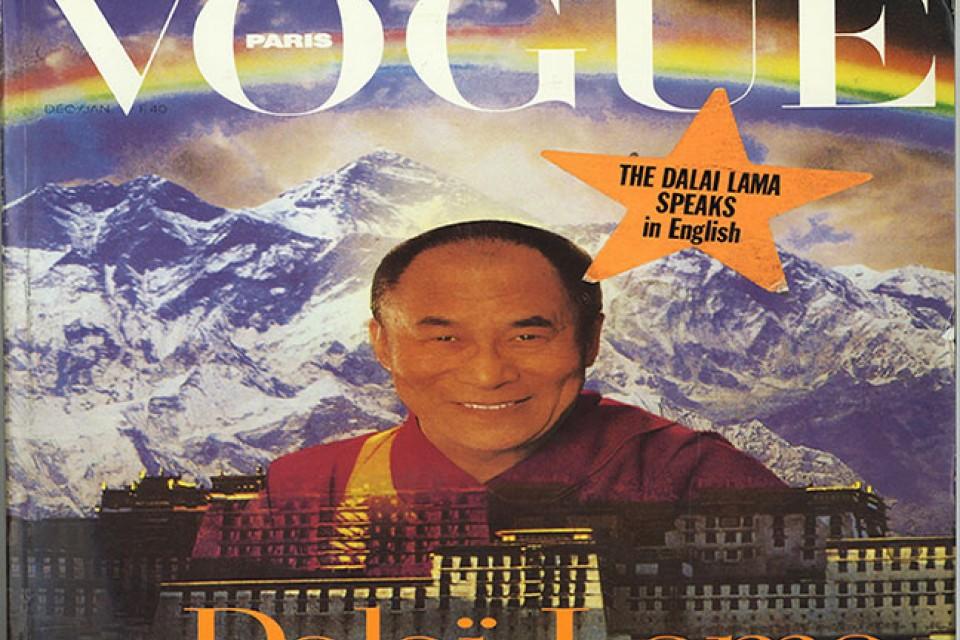

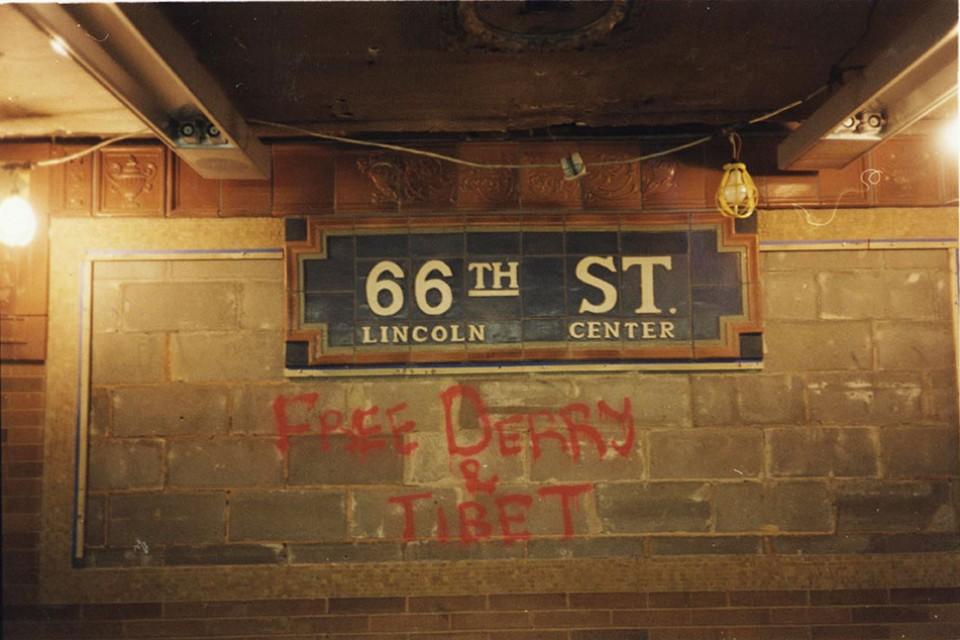

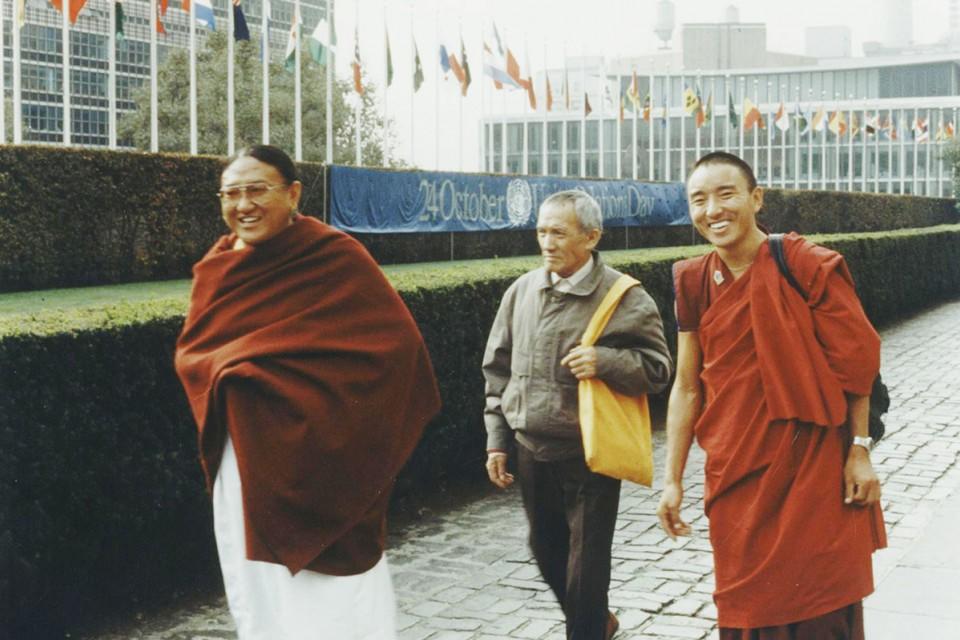

Visiting Professor of Professional Practice Meg McLagan approaches activism in research through film and cultural anthropology. She has been a recipient of grants and fellowships from the Sundance Institute, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Mellon Foundation, and the School of American Research, among others. McLagan visually documented the emergence of Tibet activism and donated select items for the “Meg McLagan Collection: The Tibet Movement in Exile, 1989-2003,” on display in Columbia University’s C.V. Starr East Asian Library until June 1 (see slideshow below). McLagan breaks down her decades-long research and where the Tibet Movement stands now.

*To make an appointment, contact Columbia’s Tibetan Studies Librarian at LH2112@columbia.edu.

Can you tell us about the research on which this new archive is based?

The materials in the archive are the result of doctoral fieldwork I conducted with Tibetan refugees and their supporters in the U.S., Switzerland, and India in the early 1990s. At that time, Tibetans faced a paradox: as special beings from “Shangri-La” they were objects of Western fascination. At the same time, they also failed, over three decades, to win recognition from the world community for their claim to political sovereignty and to be recognized as the legitimate rulers of Tibet.

Inspired by the post-Cold War political transformations taking place around the world, Tibetans in exile set about building a movement to draw attention to their cause. My research focused on the dynamics of this process and the degree to which Tibetans drew on non-Tibetan support, often engaging their fantasies of Tibet as a means of winning access. This was not a new thing. Tibet’s Mahayana Buddhist culture has long been organized around the cultivation of patrons for material support in exchange for religious teachings, and Tibetans simply incorporated Western supporters into this long-standing practice. These relationships led not just to extensive material support that helped refugees flourish in exile after China’s takeover in 1959; they also facilitated the emergence of a transnational movement that gave Tibetans a presence in the international arena dramatically out of proportion to their numbers.

How did your research on Tibet activism influence your later work?

Through my work on the Tibet Movement, I became interested in a set of questions around architectures of activism. One of the core issues that has driven my work is: How does a political movement become public? What does it take, practically and conceptually, to make a movement visible and recognized in the West?

For instance, in an early article I wrote I examined interactions between Tibetans and an American public relations consultant during a year-long campaign (“Year of Tibet”) in the U.S. and Europe. The consultant’s aim was to garner as much attention as she could for the Tibet issue and the Dalai Lama, on television and in print media (there was no Web InternetWeb at this time), and I was interested in how this was a translational process. Claims do not just exist in the world; they have to be relayed, remediated, and reframed in order to circulate. Traditional Tibetan political and religious categories do not readily conform to how the West operates, and I was interested in how Tibetans, or any group really, have to craft their movement in particular ways in order to make it visible.

I further developed these interests later, publishing essays on human rights, documentary film, activism, and most recently, co-editing a book on aesthetics and politics titled Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Politics, published by Zone Books in 2012.

Your collection includes video materials; how did they come about?

I worked on independent films in New York City before I went back to graduate school to study cultural anthropology and film at NYU. I started documenting the Tibetan community in New York while in school—everything from demonstrations in front of the United Nations to tantric initiations given by the head of the Sakya lineage, Sakya Trizin, to a lama friend taking his driver’s test in the Bronx. Eventually I made a half-hour documentary about children moved from of Tibet and resettled in Dharamsala, India, which was broadcast on public television and screened at museums, film festivals, and in a number of Tibetan resettlement sites across the U.S. It was an era when access to a camera was less ubiquitous so having one gave me a certain kind of entrée into the community and also a means to reciprocate.

As an anthropologist, what are some of the biggest culture shifts you’ve witnessed?

It is interesting for me to see how the Tibetan community in the U.S. has deepened and matured. Back in the 1990s, most Tibetans I knew had immigrated from India or Nepal, whereas today the community is much larger and more settled. Young Tibetans regard themselves as Asian Americans (as well as Tibetan), whereas the Tibetans I worked with in the 1990s saw themselves as Asians in America.

My research, and the archive that is at Starr Library, captures a hinge moment in Tibetan history when exiled Tibetans were learning what it means to be American, how American politics work, and the tactics necessary to make their claims public. I am happy that this research will be available as a resource for members of the next generation when they go to write their own scholarly accounts of the Tibetan struggle.