It’s a language without a country, a Germanic tongue in the Hebrew alphabet. Many English speakers sprinkle their speech with its most vivid words ( Oy vey! What a schlep!). For more than 1,000 years, it was the mother tongue of the millions of Jews living in central and eastern Europe. Just before World War II, more than 11 million people spoke the language, but after the scourge of the Nazis, it was nearly wiped out.

Today, perhaps fewer than a million people still speak Yiddish, and most of them are ultra-Orthodox, usually Hasidic Jews. But in the last few decades there has been a resurgence of interest in keeping the language alive beyond those who are very religious—from families who raise their children to speak Yiddish at home, klezmer music lovers, non-Jews who fall in love with the language, academics, and others. They are determined to ensure that it does not end up in the dustbin of history. Crucial to the effort is a pair of sisters who went to Barnard.

Rukhl Schaechter ’79 recently became the first woman to serve as editor of the 119-year-old Yiddish Daily Forward , the only major mainstream Yiddish publication in the world. Her sister, Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath ’79, is co-editor of the newly published, 856-page Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary , the first full-fledged English-to-Yiddish dictionary published in nearly 50 years.

Both women more or less stumbled into their roles sustaining Yiddish, though they have always had a passion for the language. Both raised their children to speak Yiddish at home and embraced the language’s vibrant cultural heritage to express their own creativity—one wrote Yiddish poetry, the other Yiddish fiction. Explains Gennady Estraikh, a professor of Yiddish studies at New York University who knows them both, “Yiddish is the language of their lives.”

The Schaechter sisters teach us a few Yiddish words for the modern ages.

• • •

The Schaechter sisters—they are 17 months apart, but graduated in the same class because Gitl started college at age 16—grew up on Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx, in a two-story brick house where only Yiddish was spoken. Those who slipped up and used English had to deposit a penny in a jar.

Their father, Mordkhe, who was born in Romania, devoted his life to Yiddish—as a teacher, author of dictionaries, and founder of organizations that promoted and preserved the language. After surviving World War II by moving from place to place with his family, he wrote a dissertation on Yiddish verbs at the University of Vienna and arrived in New York City in 1951, eventually marrying an American, Charne Saffian, who was fluent in Yiddish. From 1968 to 2002, he taught Yiddish at Columbia.

To instruct his four children in his beloved language, Mordkhe would lead them through Van Cortlandt Park, identifying each tree by its Yiddish name. He was “the pied piper,” Gitl says. Two other families on the block were also raising their children to speak the language, and the gang of young Yiddishists became a children’s club called Enge-Benge, the Yiddish equivalent of “eeny meeny miny mo.” They all went to an after-school Yiddish program five days a week down the block at Sholem Aleichem Folk School #21.

“In those days, there were still immigrants speaking Yiddish—the tailor spoke it, the newsstand sold the Yiddish Forverts ,” recalls David Fishman, who was one of those Yiddish-speaking children and is now a professor of Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary up the street from Barnard. “We had a feeling of pride: ‘Those poor kids, they don’t know Yiddish. We know our culture’s language.’”

To instruct his children in his beloved language, Mordkhe Schaechter would lead them through Van Cortlandt Park, identifying each tree by its Yiddish name. He was “the pied piper,” says his daughter Gitl. Two other families on the block were also raising their children to speak the language, and the gang of young Yiddishists became a children’s club called Enge-Benge, or “eeny meeny miny mo.”

Mordkhe was driven to help standardize the language. Without a country of native speakers, he reasoned, the language needed accepted spelling and definitions if it were to survive. He would sit in the family’s backyard at a folding table, going through stacks of Yiddish newspapers, circling interesting words, cutting them out, and stapling them to index cards. Card catalogs and shoeboxes crammed with the cards lined his office, and more were in the basement. One day, when Gitl was 12, her father asked if she wanted to earn some money helping him.

Of the four children, Gitl had the most interest in languages—at Barnard, she was a Russian major, took a Yiddish class with her father, and studied French. After graduating, she went to nursing school and began working in health care, but she also wrote Yiddish poetry, publishing a collection called Plutsemdiker Regn (Sudden Rain) in 2003.

After retiring from Columbia, Mordkhe turned his attention to his overflowing collection of Yiddish words, and he and Gitl decided to assemble a dictionary together. He managed to finish the entries for “A” before having a stroke. (He died in 2007.) Gitl vowed to finish the project, bringing in the linguist Paul Glasser, a former student of her father’s, to help. She had a job as a nursing home consultant and a husband and three children, so she worked on it when she could grab a couple hours. Three years ago, after her youngest went to college, she committed to completing it—every night after work, she would come home, park herself at the dining room table, and work until the early morning.

“It was an obsession,” she says. “I felt I really had to finish. I had to do it for my father. It was really important to all of us, not just my family but the whole Yiddish world.” The project was a labor of love—the publisher, Indiana University Press, did not give her an advance (though the project did get some financial support from the League for Yiddish).

Last summer, she finally held the completed dictionary in her hands. Weighing four and a half pounds, the book has 50,000 entries and is the result of almost two decades of work by Gitl, and many more by her father. “It is designed to carry Yiddish into the 21st century,” The New York Times said.

“The dictionary fulfills the mission Mordkhe and others had: to use the language in everyday life,” Fishman says. “It’s monumental—it will stand for a long time.” To keep Yiddish alive, words for modern concepts, inventions, and expressions need to be introduced—the smartphone, for example, has three Yiddish synonyms in the dictionary. Sometimes, Gitl had to create a word to fill a need. For “binge-watch,” she coined shlingen epizodn , which came from an existing expression in Yiddish— shlingen bikher —that means “to devour books.” “Never again will mockers and scoffers be able to say ‘there is no word for that in Yiddish,’” Fishman says.

• • •

Many—like the Schaechter sisters—are drawn to Yiddish because of their family history. Asya Vaisman Schulman ’03, for example, became interested in the language as a teen. She lived in Moscow until the age of 7, but did not learn Yiddish until she asked her parents to let her take lessons in high school from a family friend who lived near her in North Carolina. At Barnard, she created her own major that combined Yiddish and linguistics, and founded Columbia’s klezmer band. Today, she directs the Yiddish Language Institute in Amherst, Mass., and teaches Yiddish at the University of Massachusetts.

“For 1,000 years, every one of my ancestors lived in Yiddish, and their culture is expressed in this language,” she says. After the tragedy of the Holocaust, “I had the freedom to reclaim it and get to know it and my history better.”

She and her husband, Sebastian, have taught their four-year-old daughter Yiddish since birth—her husband speaks to her exclusively in Yiddish, while Schulman speaks with her in a mixture of Yiddish, Russian, and English. We are “connecting her to her past and to an amazingly rich culture,” Schulman says.

To teach her Yiddish students, Schulman often uses a feature on The Yiddish Daily Forward ’s website: the cooking shows, which feature Rukhl and Eve Jochnowitz making Jewish dishes such as blintzes, kugel, and challah. In one episode, violinist Itzhak Perlman talks in Yiddish about his mother’s recipe for potato salad with schmaltz. “Nobody had ever heard him speaking Yiddish!” Rukhl says. The most popular video demonstrates how to make gefilte fish.

The cooking instructions are narrated by Rukhl in Yiddish, but there are English subtitles, making the videos a fun language lesson. The cooking show is one of the Forward ’s most popular online elements, and it is just one way Rukhl has been working to expand the reach of the paper, which was founded in 1897 as a socialist, secular newspaper for the growing population of Jews in New York City who spoke Yiddish. (There is also an English-language edition with its own editor.) In its heyday, the paper had 250,000 readers. The print version is now published monthly and circulation numbers are small, but the Internet audience is growing and reaching into communities around the globe.

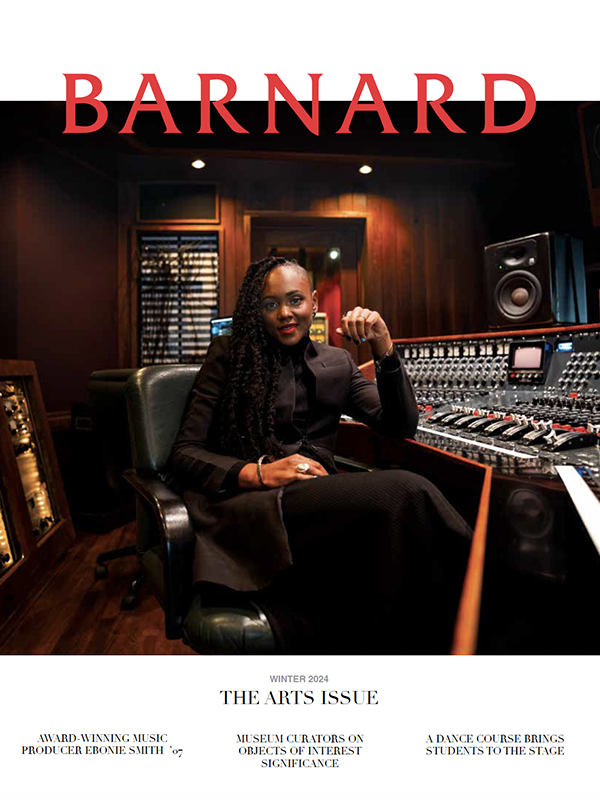

In addition to being the first female editor at the Forward , Rukhl is the first editor to have been born in the United States. She began working at the paper in 1998, when the editor asked her if she would take a position as a reporter. At the time, she was a Yiddish teacher at a Jewish day school in Riverdale, N.Y., who wrote Yiddish fiction in her spare time. When she joined the paper, she was the only woman on the editorial staff, many of whom were Holocaust survivors.

Today, a strong audience for the newspaper is Hasidic Jews, who speak Yiddish as their daily language to separate themselves from American culture. (They don’t use Hebrew for ordinary conversation because they regard it as a holy language.) They frequent the paper’s website, usually in secret, as their deeply religious community looks unfavorably on reading secular publications. But the Forward is “a vital lifeline to the world outside their own,” says Rukhl, who sees traffic to the paper’s website dip during Shabbat, when religious Jews don’t use electricity. She has brought in Hasidic Jews to write blogs—without using their real names—to further connect to that community, which makes up 90 percent of today’s Yiddish speakers, according to Estraikh, the NYU professor. There are thriving Hasidic communities in Brooklyn, Israel, Antwerp, London, and Montreal.

To others, Yiddish is attractive for a host of reasons. “For some, it’s a quest for Jewishness. For others, what is appealing is the rich culture—the literature, theatre, music, and history associated with it,” says Estraikh, citing the Yiddish writers Isaac Bashevis Singer and Sholem Aleichem. There is also “an element of being an underdog. You feel you are a fighter. I even know families in which neither parent is Jewish and they use Yiddish as a first language for their children. People really fall in love.” There are summer retreats where participants speak only Yiddish for a week and numerous events around klezmer music, which is associated with Yiddish culture.

For Nikki Charlap ’17, speaking Yiddish offers a way to connect with her family’s past. She has taken “Elementary Yiddish” at Columbia for two semesters and is doing an independent study to further improve her skills. “Learning Yiddish has made me feel more in touch with my roots as a Jewish woman,” says Charlap, whose grandparents speak Yiddish. “It’s been pretty cool formally learning all the phrases I heard growing up.”

The call to Yiddish is drawing many more people to Gitl’s massive dictionary than she anticipated. The first and second printings—2,200 copies—sold out in nine months. A third printing is underway. It is thrilling, she says, to know people are using the book and employing words she coined. When she heard a friend use the Yiddish word for binge-watching in conversation, it confirmed for her that “the language is alive.”

On a more personal scale, Gitl and Rukhl have succeeded in giving their children a love of the language. They have six adult children between them, and all of them speak Yiddish to their mother when they call home. And the flame of Yiddish is being passed to the next generation: Gitl has an 18-month-old grandson, and his first language is Yiddish. •

What’s Yiddish for “Selfie”?

To keep a language alive, new words constantly need to be coined. Having a conversation today in Yiddish requires words for everything from “email” to “feminism.” For the new Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary she co-edited, Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath ’79 created a number of words and institutionalized others that had already evolved.

New words need to have a Yiddish sound and be user-friendly. A case in point: She and her co-editor wanted to create a way to say “I have butterflies in my stomach” in Yiddish. Their solution was to co-opt an existing Yiddish expression, se tsitern mir di kishkes , which means “my intestines are trembling.”

Here are some other Yiddish words for modern expressions from the dictionary. Listen to co-editor Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath ’79 share official pronunciations.

binge-watch ShLÍNGEN EPIZÓDN

G-string DOS LÉNDN-BENDL

hack into ARÁYNDRINGEN <ARÁYNHAKN> IN

newsfeed DER NÁYESShTROM

selfie DOS ZÍKhELE

Twitter DER TVÍTER

to tweet TSVÍT(Sh)ERN

transgender woman DI TRÁNSFROY

egalitarianism DER EGALITARÍZM

empowerment DOS BAKÓYEKhN

feminism DER FEMINÍZM

gender gap DER ÉR-ZÍ-KhÍLEK

maternity leave DER KÍMPET-ÚRLOYB

women’s lib DI FRÓYENFRAY

women’s studies FRÓYEN-LIMÚDIM